Friday, April 24, 1998 Section D★★

Creativity Public Speaking Article, Houston Chronicle

Can it be taught? What

|

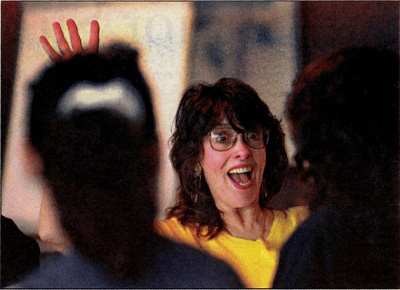

For example, a seminar for high school students and teachers focused on the idea of "How can we make learning in the classroom more fun?" Wishful thinking led one of the students to say, "Let's get rid of the teachers." The off-hand comment sparked a spirited discussion that led to a creative way to tackle the problem. The group decided that once a month, a student or team of students would take turns conducting the lesson and the teacher would become part of the student group. "Once you get outside your normal pattern of thinking, you go out in new directions," says Tanner. McKnight, an actress and communications specialist who teaches seminars around the country on the art and power of creative communication, favors performance techniques such as improvisation and focused concentration taken from the acting world. She believes anyone can learn to be creative if they open up and become more willing to take risks. "First you have to have a willingness or an interest in being more creative about life," she says. "That means you have to overcome your fears of it." In a workshop prior to the start of the convention, McKnight led a group through a series of games such as throwing stuffed animals in syncopated time and mirroring each other's movements to encourage spontaneity, observation and dealing with energy and all the senses. The session ended with team improvisations to get the group to begin learning to think quickly on their feet. "What we're trying to do is to get you to open up to the process of creativity," she says. "The only way I know to do that is to participate in some kind of creative activity." She encourages those who are timid about the creative process to first start with a fun physical activity, such as yoga or dancing lessons. "Do the things that are fun for you, so that you open your physical willingness to do things," she says. "This begins to work with the mind, because once you open up physically, you start to open |

emotionally and mentally." "Then begin to take any kind of risk that allows you to move out of your comfort zone," she says. (She favors taking an improvisation class at a local comedy club as a way to improve creative powers.) "Nike is making millions of dollars selling shoes by telling people, 'Just Do It' because most people don't just do it," she says. "People just don't have the energy or the cultural reinforcement to be creative. Our society does not support creativity, originality or risk-taking." Dale Clauson, a Houston board member of the American Creativity Association and co-chair of its convention, says it's not surprising that most people are afraid to be creative because the first reaction to any new idea is usually negative. He says when you ask a kid, "What do you think of my idea?", most responses are positive. But by age 16, half will respond negatively and half will respond positively. By the time that person has reached adulthood, he or she is likely to discourage creative thinking. More than 85 percent of adults will tell you what's wrong with the idea rather than offer any positive feedback. So Clauson, who heads a company called Strategic Innovations that helps corporations attack problems with creative thinking, keeps a piece of paper in his wallet with the letters P.I.N., which stand for "positive", "interesting" and "negative." When someone presents an idea, he looks at its positive aspects before getting to ways it could be improved. "I say something like, 'It's a good idea. I like it.' Then we get to the point of 'Have you thought about doing this?' That addresses the negative in a positive way." Clauson also cites research that indicates the average child asks 143 questions a day whereas the average adult asks only six questions a day. "Creative people are the ones who keep questioning and are positive about their ideas," he says. |